Bill S.’s paraSITE shelter. He requested as many windows as possible, because “homeless people don’t have privacy issues, but they do have security issues. We want to see potential attackers, we want to be visible to the public.” Six windows are placed at eye level for when Bill is seated and six smaller windows for when Bill is reclining.

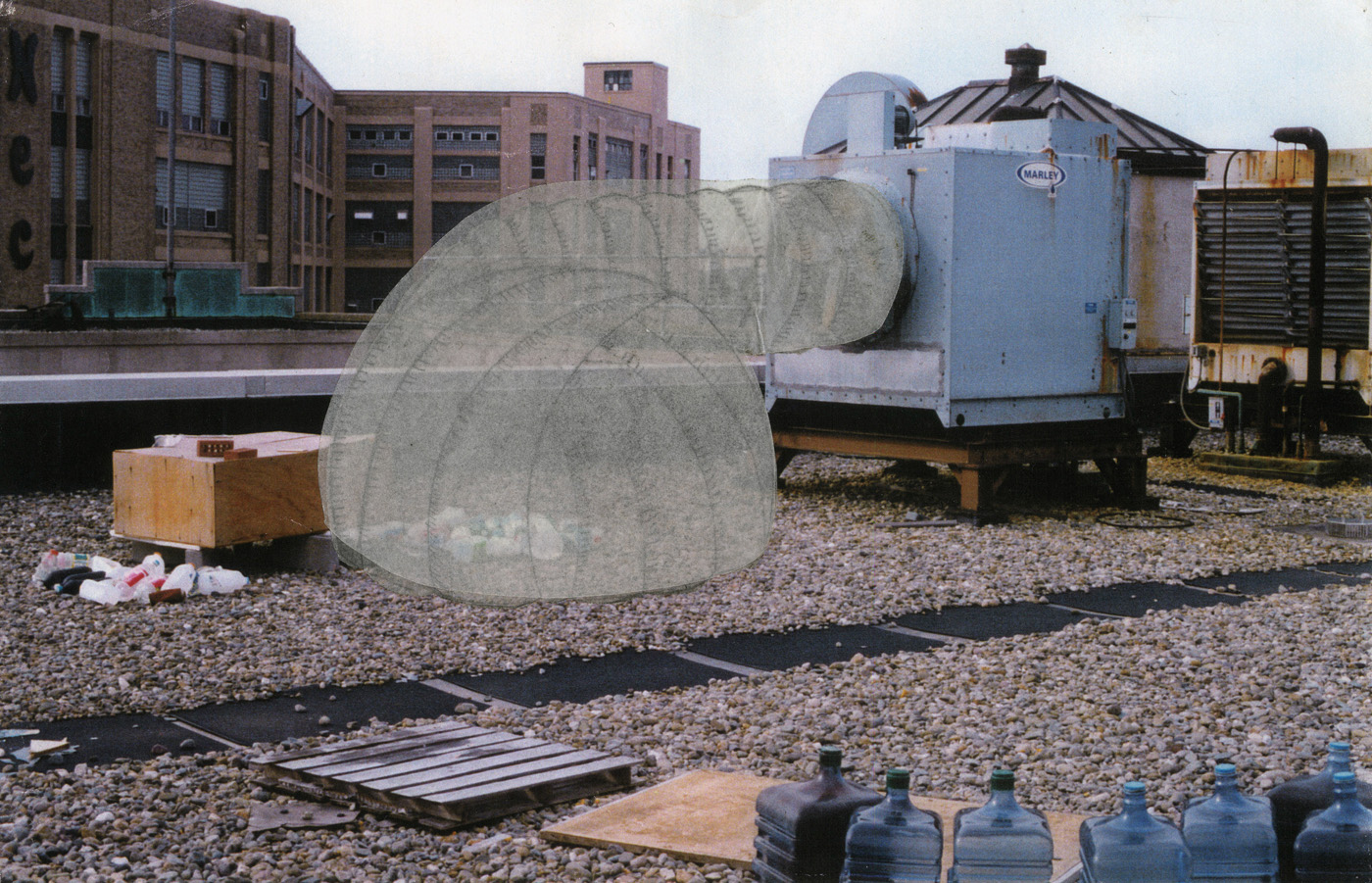

George L.’s paraSITE shelter. Made on a budget of $5.00 from trash bags, ZipLoc bags, and clear waterproof packing tape. George requested a system of “ribs” that would be made of semi-translucent trash bags. In between the ribs, he wanted windows to expose the “meat” between the bones.

The windows are made of Ziploc sandwich bags and serve as pockets to display personal items and signage for the public. Privacy and publicity can be regulated by adding or removing objects.

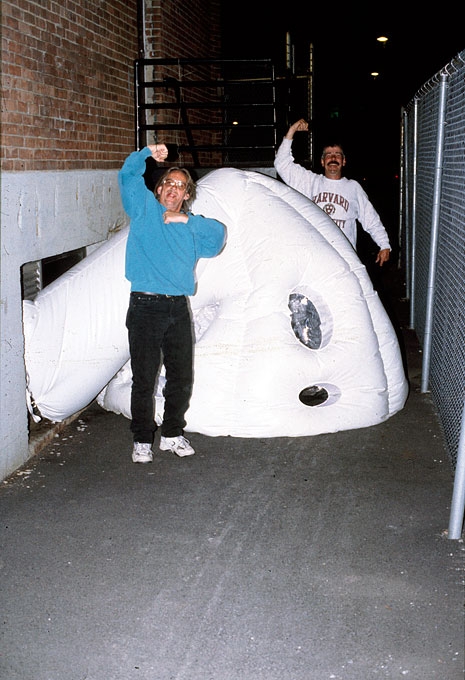

Bill S., Freddie F., and George L. with Freddie’s paraSITE shelter. An avid science fiction fan, Freddie requested a shelter in the shape of Jabba the Hutt.

Joe H. using his paraSITE shelter in February 2000. Joe is a homeless man who lived on the streets near Battery Park City in Manhattan. In the 1970s, he became a contractor and was responsible for building over fifteen buildings in Brooklyn. He was diagnosed with cancer in the 1980s after being exposed to Agent Orange while serving in the Air Force in Vietnam. After forty-seven different operations to treat the cancer, the Veteran’s Association of America ceased paying his medical bills and he went bankrupt.

Michael M. using his paraSITE shelter on 26th Street and 9th Avenue in New York. Michael was a homeless man who worked for the United Homeless Organization. He wanted to respond to an obscure anti-tent by-law being enforced by the Giuliani administration, which stated that any structure 3.5 feet or taller set up on city property would be considered an illegal encampment.

We designed his shelter to be closer to the ground, more like a sleeping bag or some kind of body extension. Thus, if questioned by the police, he could argue that the law did not apply because the shelter was not, in fact, a tent. On more than one occasion, Michael was confronted by police officers. After measuring his shelter, the officers moved on.

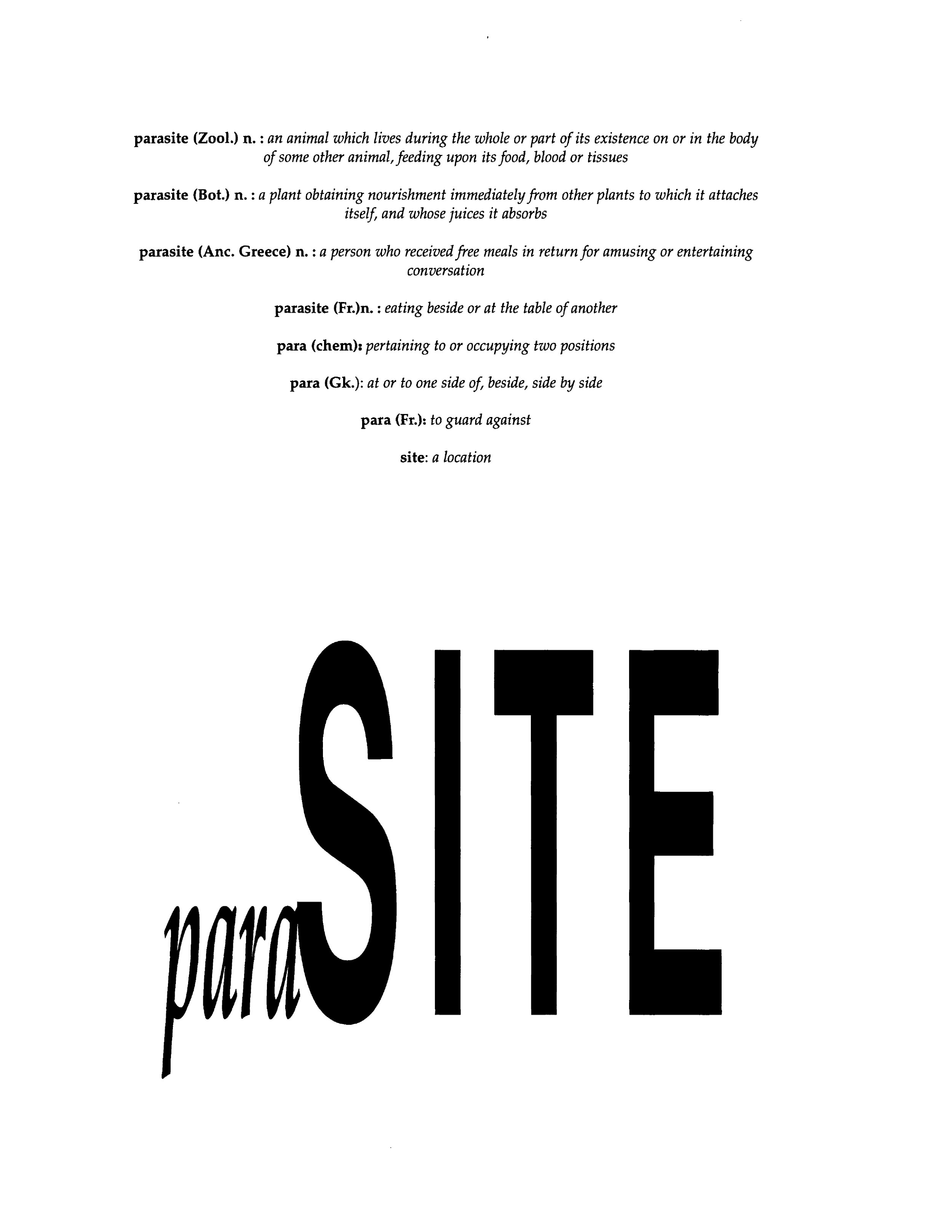

The chosen title, paraSITE, is layered in its meaning, its derivation, and its understanding.

paraSITE borrows its prefix from the French definition of para, which translates to English as "guard against". Para, when it joins its suffix chute as parachute translates to "guard against falling." The French word for umbrella, parapluie translates to "guard against rain". The prefix thus has a history in describing protective or preventive devices, or objects related to the tasks of survival and rescue.

The suffix, site, refers to a place or location. We can interpret this word, both prefix and suffix to mean "guard against a site", the act of holding or occupying a space. But in the context of a nomadic project based on the ephemeral the interpretation must also turn to "guard against situating" or guard against "becoming a site"; the nomad moves on, deterritorializing themself.

Looking at the work, one can make a physical association to a parachute, a folding umbrella like fabric device with chords supporting a harness or straps for allowing a person to float down safely through the air from a great height, rendered effective by the resistance of the air that expands it during the descent and reduces the velocity of its fall.

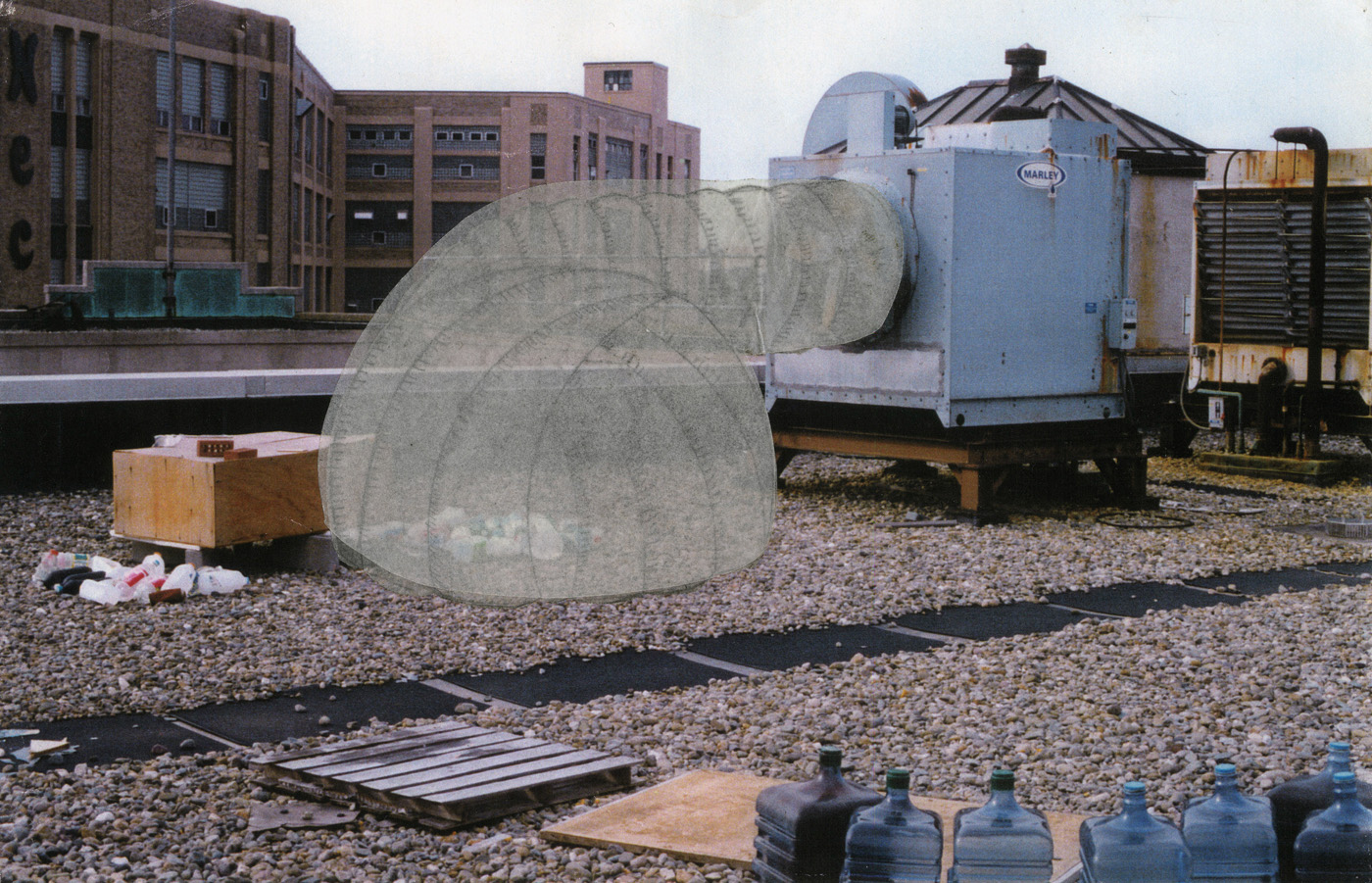

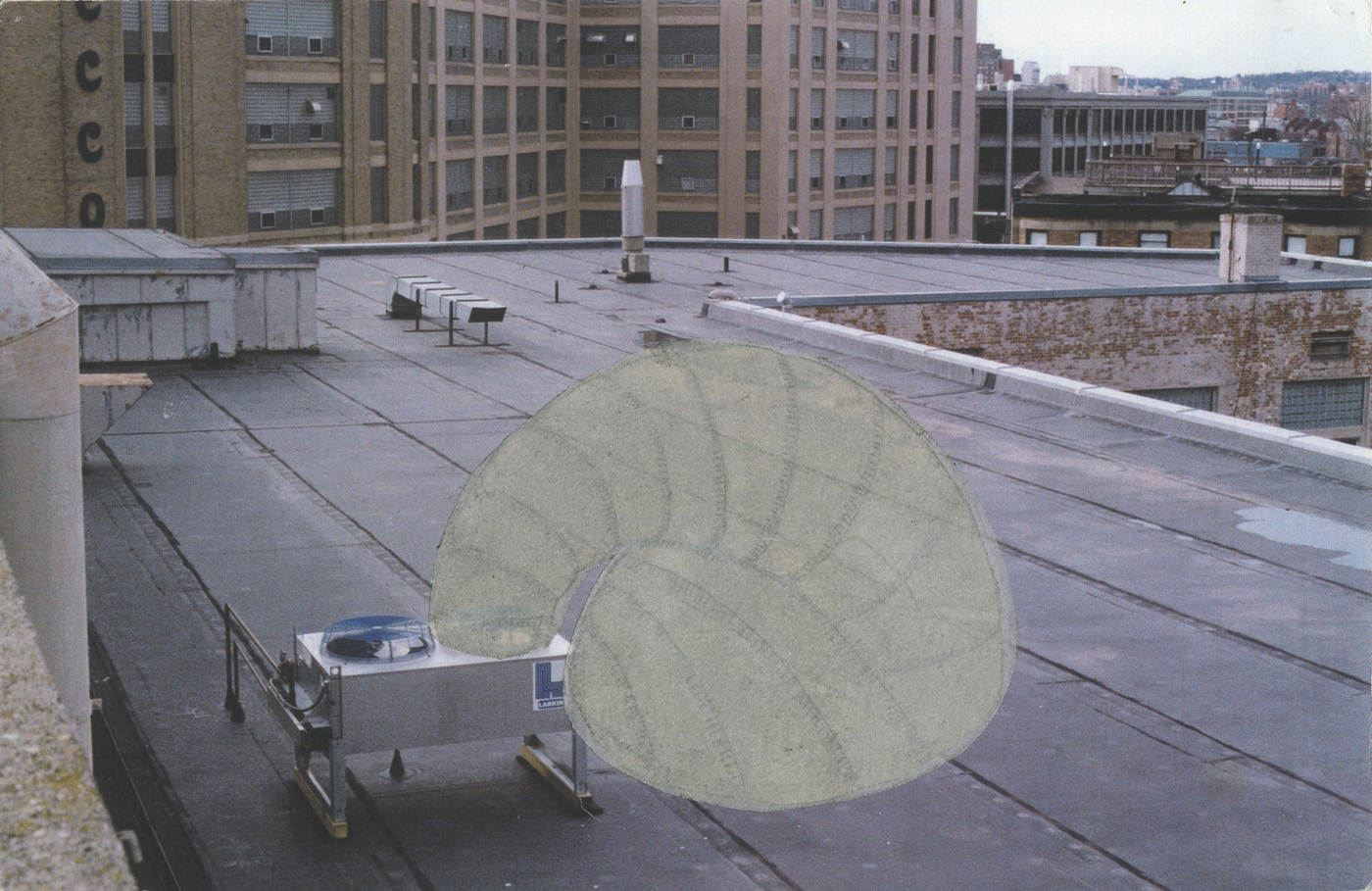

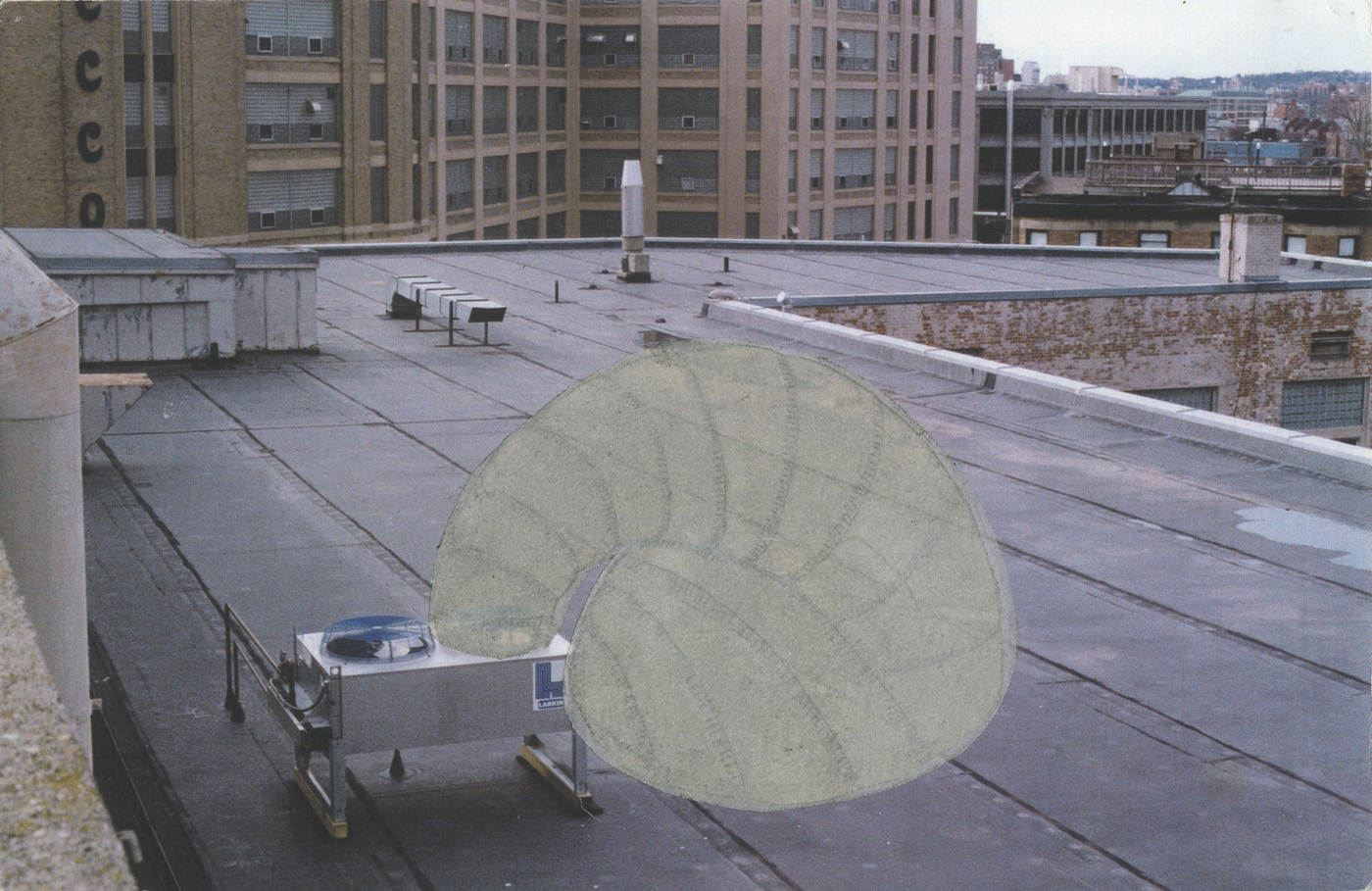

paraSITE is similar, in that it too is a membrane structure relying upon the resistance of air in its use. Inflated by the exterior fan ducts of architecture, it provides a new space to occupy, amplifying the harsh reality of life on the street, while offering refuge.

paraSITE scandalizes the above notions of safety or rescue while simultaneously making use of them. While there is an element of invention, of genuine survival strategy applied to this project, it also is presented as an act of desperation, an unacceptable approach to the problem as a design or as a solution. It is a project made at the intersection of problem-solving and trouble-making.

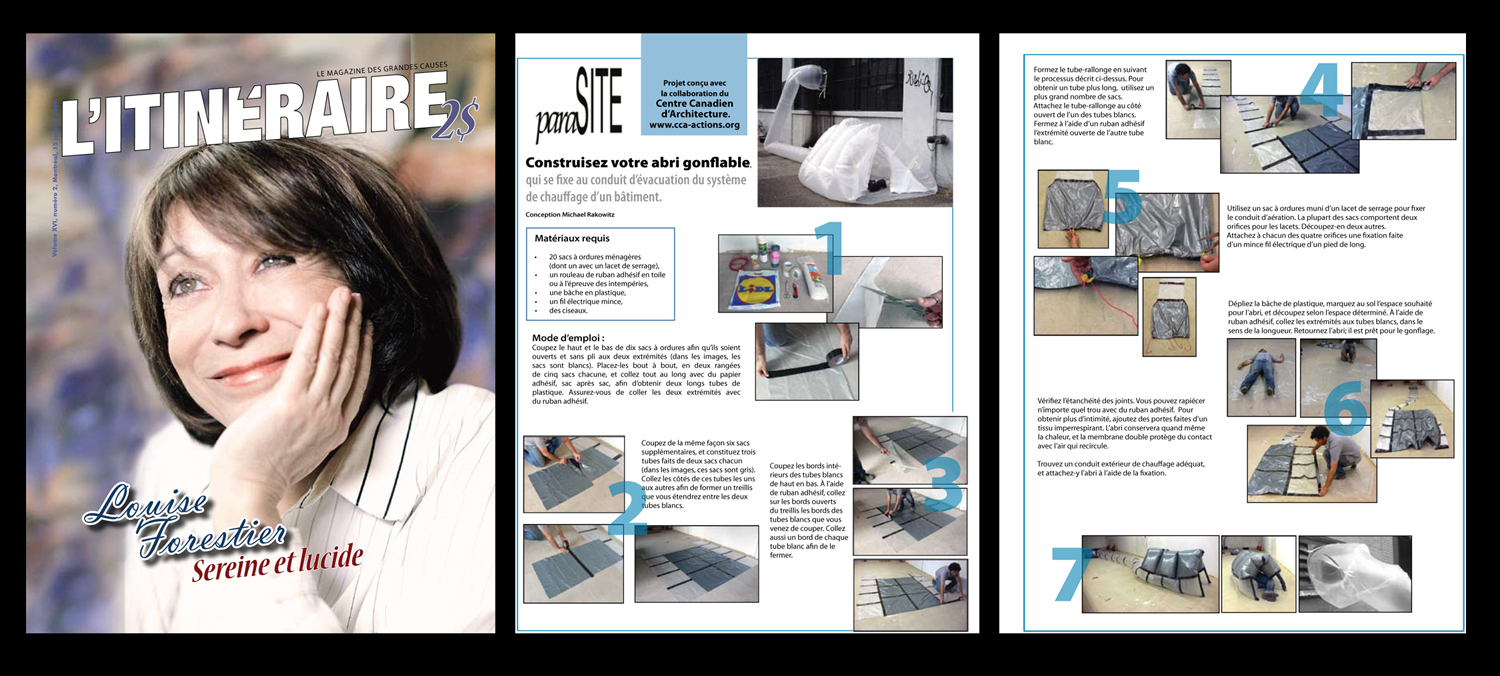

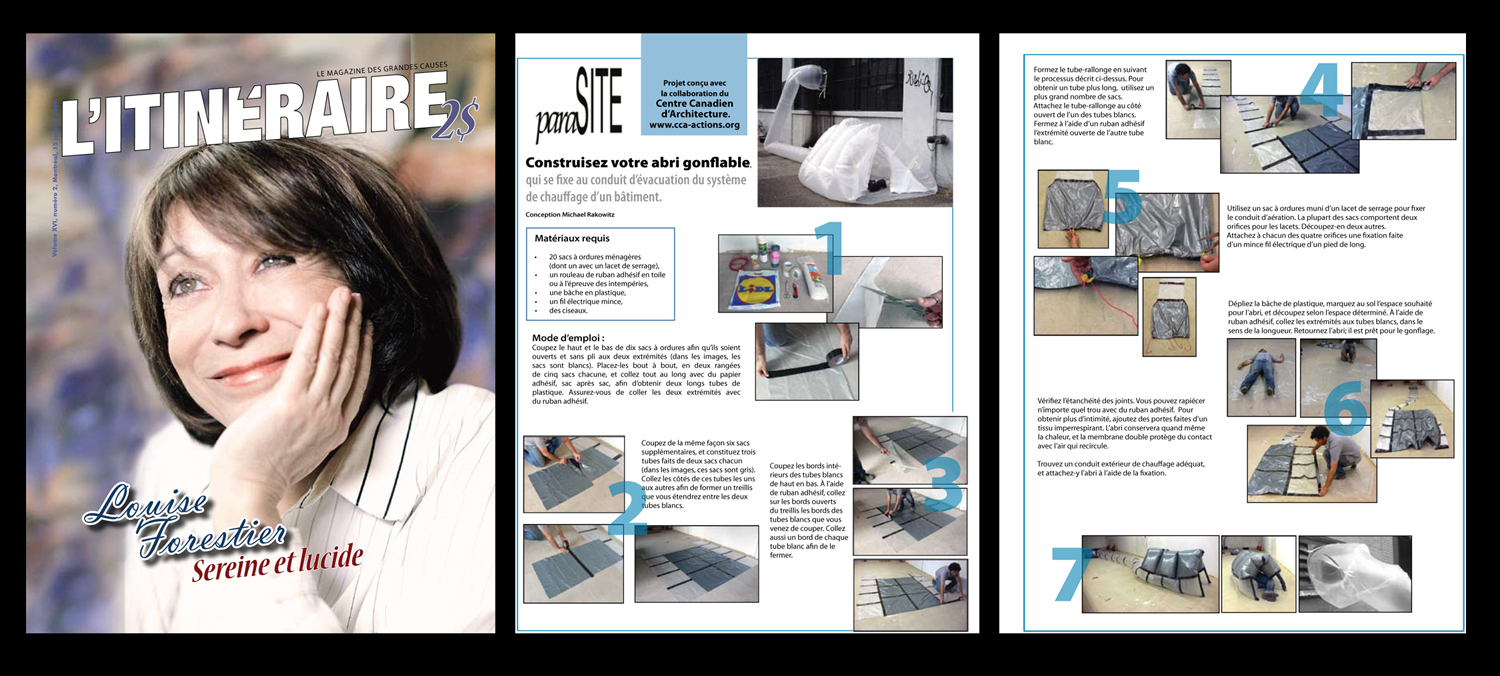

Step-by-step, DIY instructions on how to build a paraSITE shelter, printed in L’Itineraire, a Montréal-based magazine that features some articles written by homeless people, who also sell the magazine to passersby on the street. Published in January 2009, with plans to print the same instructions in Motz, a Berlin-based newspaper published and sold by homeless people, and also in a similar publication in London, called The Pavement.

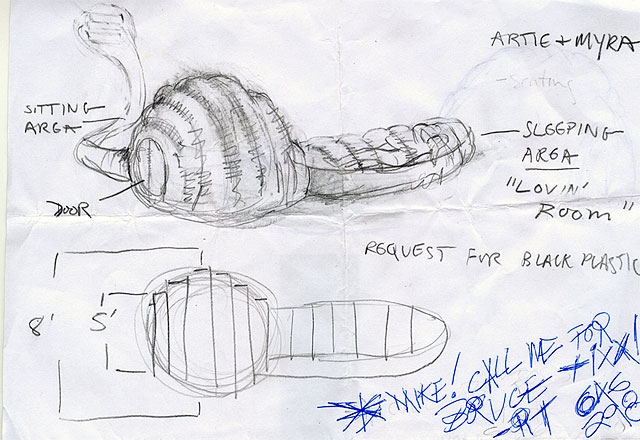

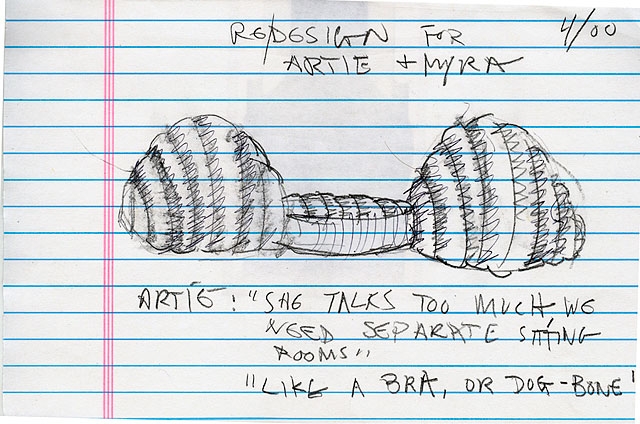

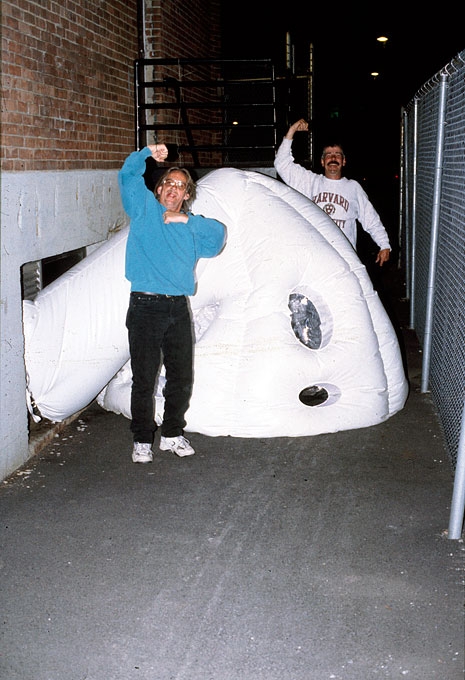

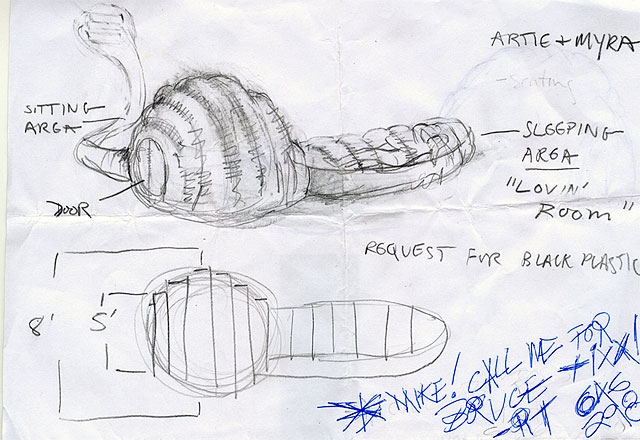

Design process sketches for a shelter built for Artie, a 62-year-old homeless man living near Madison Square Garden. Artie often stands in line for concert tickets at the request of scalpers. For his paraSITE, Artie requested a domed sitting space for himself and his girlfriend, Myra, connected to a lower, intimate sleeping area for two, “the lovin’ room.”

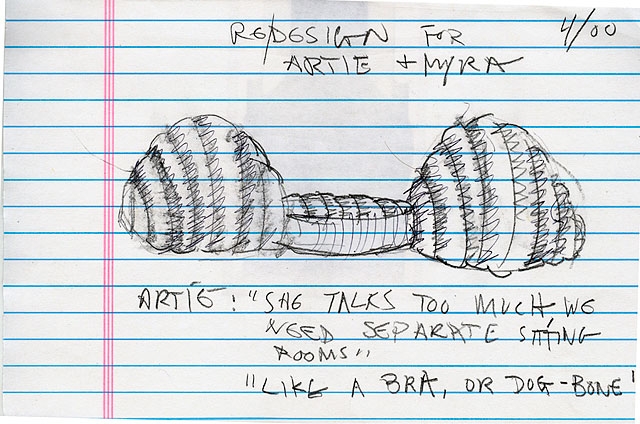

Halfway through construction, I received a call from Artie ordering me to stop building. “Myra talks way too much!” he explained, and asked that I make two domed sitting areas, separated by the lovin’ room. “It should look like a bra, or a dogbone.”

Bill S.’s paraSITE shelter. He requested as many windows as possible, because “homeless people don’t have privacy issues, but they do have security issues. We want to see potential attackers, we want to be visible to the public.” Six windows are placed at eye level for when Bill is seated and six smaller windows for when Bill is reclining.

George L.’s paraSITE shelter. Made on a budget of $5.00 from trash bags, ZipLoc bags, and clear waterproof packing tape. George requested a system of “ribs” that would be made of semi-translucent trash bags. In between the ribs, he wanted windows to expose the “meat” between the bones.

The windows are made of Ziploc sandwich bags and serve as pockets to display personal items and signage for the public. Privacy and publicity can be regulated by adding or removing objects.

Bill S., Freddie F., and George L. with Freddie’s paraSITE shelter. An avid science fiction fan, Freddie requested a shelter in the shape of Jabba the Hutt.

Joe H. using his paraSITE shelter in February 2000. Joe is a homeless man who lived on the streets near Battery Park City in Manhattan. In the 1970s, he became a contractor and was responsible for building over fifteen buildings in Brooklyn. He was diagnosed with cancer in the 1980s after being exposed to Agent Orange while serving in the Air Force in Vietnam. After forty-seven different operations to treat the cancer, the Veteran’s Association of America ceased paying his medical bills and he went bankrupt.

Michael M. using his paraSITE shelter on 26th Street and 9th Avenue in New York. Michael was a homeless man who worked for the United Homeless Organization. He wanted to respond to an obscure anti-tent by-law being enforced by the Giuliani administration, which stated that any structure 3.5 feet or taller set up on city property would be considered an illegal encampment.

We designed his shelter to be closer to the ground, more like a sleeping bag or some kind of body extension. Thus, if questioned by the police, he could argue that the law did not apply because the shelter was not, in fact, a tent. On more than one occasion, Michael was confronted by police officers. After measuring his shelter, the officers moved on.

The chosen title, paraSITE, is layered in its meaning, its derivation, and its understanding.

paraSITE borrows its prefix from the French definition of para, which translates to English as "guard against". Para, when it joins its suffix chute as parachute translates to "guard against falling." The French word for umbrella, parapluie translates to "guard against rain". The prefix thus has a history in describing protective or preventive devices, or objects related to the tasks of survival and rescue.

The suffix, site, refers to a place or location. We can interpret this word, both prefix and suffix to mean "guard against a site", the act of holding or occupying a space. But in the context of a nomadic project based on the ephemeral the interpretation must also turn to "guard against situating" or guard against "becoming a site"; the nomad moves on, deterritorializing themself.

Looking at the work, one can make a physical association to a parachute, a folding umbrella like fabric device with chords supporting a harness or straps for allowing a person to float down safely through the air from a great height, rendered effective by the resistance of the air that expands it during the descent and reduces the velocity of its fall.

paraSITE is similar, in that it too is a membrane structure relying upon the resistance of air in its use. Inflated by the exterior fan ducts of architecture, it provides a new space to occupy, amplifying the harsh reality of life on the street, while offering refuge.

paraSITE scandalizes the above notions of safety or rescue while simultaneously making use of them. While there is an element of invention, of genuine survival strategy applied to this project, it also is presented as an act of desperation, an unacceptable approach to the problem as a design or as a solution. It is a project made at the intersection of problem-solving and trouble-making.

Step-by-step, DIY instructions on how to build a paraSITE shelter, printed in L’Itineraire, a Montréal-based magazine that features some articles written by homeless people, who also sell the magazine to passersby on the street. Published in January 2009, with plans to print the same instructions in Motz, a Berlin-based newspaper published and sold by homeless people, and also in a similar publication in London, called The Pavement.

Design process sketches for a shelter built for Artie, a 62-year-old homeless man living near Madison Square Garden. Artie often stands in line for concert tickets at the request of scalpers. For his paraSITE, Artie requested a domed sitting space for himself and his girlfriend, Myra, connected to a lower, intimate sleeping area for two, “the lovin’ room.”

Halfway through construction, I received a call from Artie ordering me to stop building. “Myra talks way too much!” he explained, and asked that I make two domed sitting areas, separated by the lovin’ room. “It should look like a bra, or a dogbone.”