My grandfather Nissim Isaac David and family

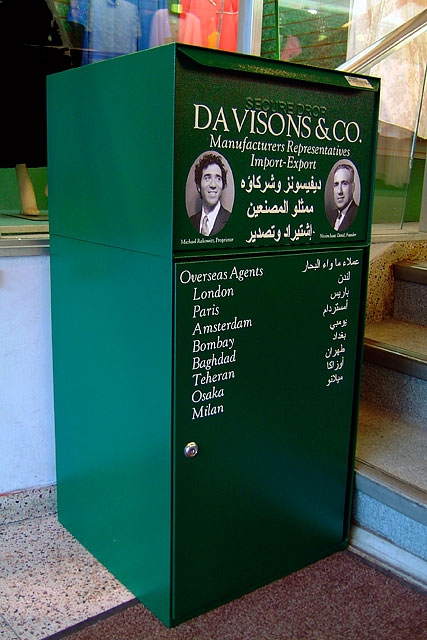

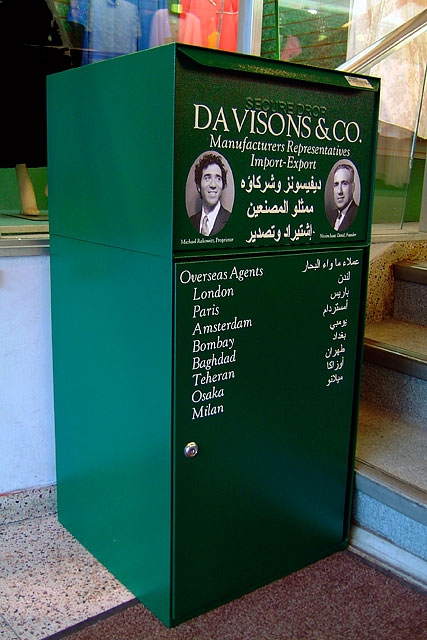

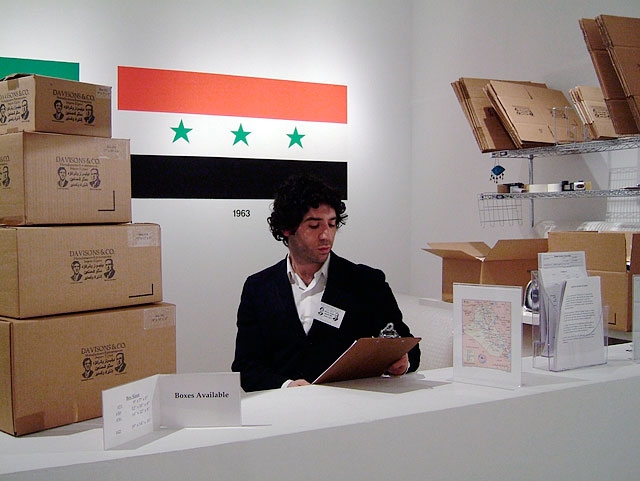

Davisons & Co, Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn

Dropbox

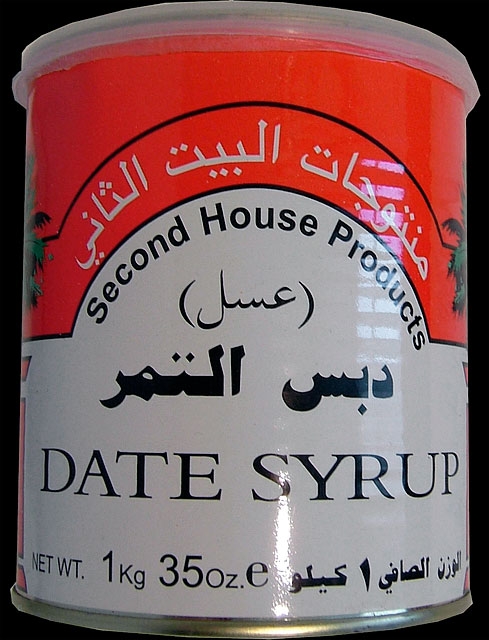

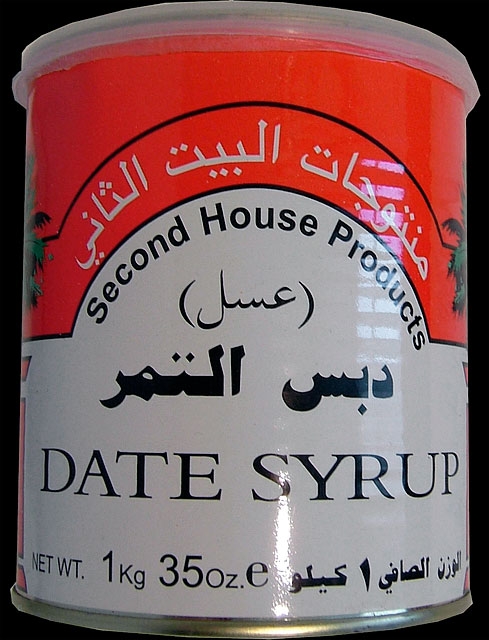

In the store I displayed pictures of the harvest, which Al Farez sent me. The dates were packed and ready to ship via Jordan in early October. They traveled by truck along the most dangerous road in the country, then waited in a line of cars at the Jordanian border that was reported to be four days long, as hundreds of thousands of Iraqis tried to flee the worsening sectarian violence. After sending the truck back to Baghdad for a radiation certificate, the Jordanians finally refused the cargo as a security concern. The exhausted truck driver then headed north to Syria and dropped off the dates at the airport in Damascus, where they were to get on a plane to Egypt, then onward to the US. The shipment was held there for a week, and was by then so blistered from three hot weeks in a truck that Al Farez deemed it unacceptable for export. So the shipment died in Syria.

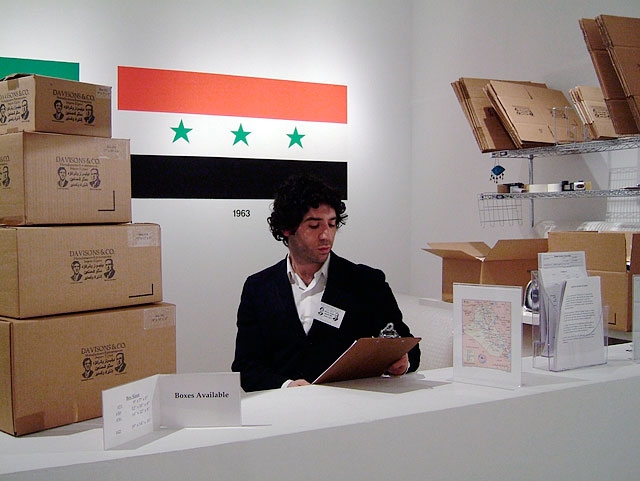

Meanwhile, the store opened, empty of Iraqi dates for the time being, but selling four California varieties derived from Iraqi seed. All along, the story of the dates and daily updates were communicated to customers frequenting the store. The dates suddenly became a surrogate, traveling the same path as Iraqi refugees. The store became a place where that crisis and its affiliated narrative was being disseminated—hardly the exchange a customer would expect.

Customer reactions were as layered as my gesture of opening the store. Many, like Shamoon Salih (left), an Iraqi Jew who left in 1960, spoke from the position of nostalgia and memory, which always seemed to be a window into the pain or the trauma of having to leave Iraq, or being unable to return in the current context. Others came in to speak about possible business ventures, like Ibrahim, from Kurdistan, and Omar, from Egypt, who wanted to export white American paint to Iraq, where it was a much sought after commodity.

Another kind of customer interaction occurred when Hana Ali and her family came to the store to ship boxes of household items and toys to their relatives in Diwanya, where a cousin had just been killed by insurgents. When an American couple walked in, Hana immediately asked them what they thought of the news, then current, that Hussein had been sentenced to death. A discussion ensued that lasted over an hour. There were many, many other such interactions, and thus the project began to function as a community space and social network where I receded and customers reacted to each other, the possibility of their meeting facilitated and choreographed through the appearance of this strange store.

After the initial shipment of dates met their untimely end, Al-Farez remained determined to stock my store, arranging for 10 boxes to be airlifted out of Baghdad direct to New York City via DHL. For three weeks the small parcel underwent inspection by Homeland Security, US Customs and Border Patrol, the USFDA and the USDA. At one point a US Customs agent determined that the shipment was illegal since we were “at war with Iraq.” Finally the dates reached the store and customers flocked, eager to try the fruit that had now interrogated and scandalized every government agency from Baghdad to Damascus to New York. A fruit that asked questions.

Shamoon returned, for a taste of what he called thikra, which means memory or nostalgia. “It’s for when you are homesick, when you miss your home,” he said. He slowly put his first date in his mouth, closed his eyes, smiled, and softly said, “this is 46 years in the making.”

When I told Al Farez how happy the customers were to finally receive the dates, they asked me to take pictures of those who had bought them. Here are a few of the many.

My grandfather Nissim Isaac David and family

Davisons & Co, Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn

Dropbox

In the store I displayed pictures of the harvest, which Al Farez sent me. The dates were packed and ready to ship via Jordan in early October. They traveled by truck along the most dangerous road in the country, then waited in a line of cars at the Jordanian border that was reported to be four days long, as hundreds of thousands of Iraqis tried to flee the worsening sectarian violence. After sending the truck back to Baghdad for a radiation certificate, the Jordanians finally refused the cargo as a security concern. The exhausted truck driver then headed north to Syria and dropped off the dates at the airport in Damascus, where they were to get on a plane to Egypt, then onward to the US. The shipment was held there for a week, and was by then so blistered from three hot weeks in a truck that Al Farez deemed it unacceptable for export. So the shipment died in Syria.

Meanwhile, the store opened, empty of Iraqi dates for the time being, but selling four California varieties derived from Iraqi seed. All along, the story of the dates and daily updates were communicated to customers frequenting the store. The dates suddenly became a surrogate, traveling the same path as Iraqi refugees. The store became a place where that crisis and its affiliated narrative was being disseminated—hardly the exchange a customer would expect.

Customer reactions were as layered as my gesture of opening the store. Many, like Shamoon Salih (left), an Iraqi Jew who left in 1960, spoke from the position of nostalgia and memory, which always seemed to be a window into the pain or the trauma of having to leave Iraq, or being unable to return in the current context. Others came in to speak about possible business ventures, like Ibrahim, from Kurdistan, and Omar, from Egypt, who wanted to export white American paint to Iraq, where it was a much sought after commodity.

Another kind of customer interaction occurred when Hana Ali and her family came to the store to ship boxes of household items and toys to their relatives in Diwanya, where a cousin had just been killed by insurgents. When an American couple walked in, Hana immediately asked them what they thought of the news, then current, that Hussein had been sentenced to death. A discussion ensued that lasted over an hour. There were many, many other such interactions, and thus the project began to function as a community space and social network where I receded and customers reacted to each other, the possibility of their meeting facilitated and choreographed through the appearance of this strange store.

After the initial shipment of dates met their untimely end, Al-Farez remained determined to stock my store, arranging for 10 boxes to be airlifted out of Baghdad direct to New York City via DHL. For three weeks the small parcel underwent inspection by Homeland Security, US Customs and Border Patrol, the USFDA and the USDA. At one point a US Customs agent determined that the shipment was illegal since we were “at war with Iraq.” Finally the dates reached the store and customers flocked, eager to try the fruit that had now interrogated and scandalized every government agency from Baghdad to Damascus to New York. A fruit that asked questions.

Shamoon returned, for a taste of what he called thikra, which means memory or nostalgia. “It’s for when you are homesick, when you miss your home,” he said. He slowly put his first date in his mouth, closed his eyes, smiled, and softly said, “this is 46 years in the making.”

When I told Al Farez how happy the customers were to finally receive the dates, they asked me to take pictures of those who had bought them. Here are a few of the many.